Some Jazz Records: Yusef Lateef (1960s) Clippings

Comments on recordings from musicians and other actors of the jazz scene. Random and not-so-random listening cues from the archives.

Andy Kirk and His Twelve Clouds of Joy, Christopher Columbus/Froggy Bottom, Decca 729, 1936, 10" 78 rpm.

Down Beat once ran a series titled "Stereo Shopping with…" featuring musicians discussing hi-fi equipment. Yusef Lateef was the subject of a 1960 installment. "Yusef Lateef, who started playing alto and tenor saxophones in a Detroit high school in 1937, has been fascinated with the sound of sound since before he got his first record player at the age of 19," the opening read. "It was a little two-tube portable with a miniature speaker. Through it he heard his first records, old Deccas like Count Basie’s 'Jive at Five' and Andy Kirk’s 'Moten Swing' and 'Froggy Bottom' featuring Mary Lou Williams and tenor saxophonist Dick Wilson, an early favorite of Lateef’s."

Dizzy Gillespie, Salt Peanuts/Hot House, Guild 1003, 1945, 10" 78 rpm.

Originally a Detroit resident, Yusef Lateef made a temporary move to New York in the mid-1940s. "Charlie Parker’s influence pervaded everyone’s thinking who was really trying to evolve in their playing at that time," Lateef told Down Beat in 1965. "I had heard 'Hot House,' but I hadn’t heard too much because it was so new." Parker recorded the bebop classic in 1945 with Dizzy Gillespie. "I had heard Sonny Stitt though. He was with the 'Bama State Collegians when I joined them. At that time he was playing more like Benny Carter, but then Charlie Parker came on the scene, and this transition took place in Sonny. His playing evolved very rapidly. So I was exposed to him and to Dexter Gordon too."

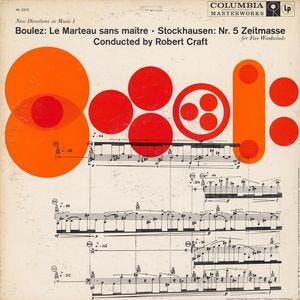

Pierre Boulez, Le marteau sans maître/Karlheinz Stockhausen, Nr. 5 Zeitmasse for Five Woodwinds, conducted by Robert Craft, Columbia Masterworks ML 5275, 1958, LP; and Aretha Franklin, Laughing on the Outside, Columbia CL 2079 (CS 8879), 1963, LP.

To conclude a 1964 Down Beat blindfold test, Leonard Feather asked Yusef Lateef what records he would give top ratings to if he didn’t reject the idea of rating music. "Among the outstanding records—Zeitmasse No. 5 by Karlheinz Stockhausen, that’s the most impressive thing I’ve heard in the last two years," Lateef said. "And Aretha Franklin, the album with 'Skylark' in it; for jazz that was one of the most impressive." When he spoke to Down Beat again the next year, Lateef also mentioned Stockhausen. "I’m trying to evolve the technical aspects of my music—form, melody, and harmony," he said. "I’ve been studying atonality for the past three years, and I feel that atonality and that which is beyond atonality will give new life to music. What I mean when I say 'beyond atonality' is the idiom that, say, Karlheinz Stockhausen uses. […] Personally, I think music written in the tonal idiom has become monotonous more or less, so there’s a need for an evolution. The resources of tonality are practically exhausted, I feel. I know this. My ears, my understanding of music, tell me this."

André Hodeir, Since Debussy: A View of Contemporary Music (New York: Grove, 1961).

In 1963, French magazine Jazz Hot published interviews with the frontline of the Cannonball Adderley group, among whom figured Yusef Lateef. The saxophonist told François Postif that he owed his strong interest in contemporary classical music’s most recent developments—which he saw as a nearly complete break with the past—in large part to the reading of André Hodeir’s Since Debussy: A View of Contemporary Music. Hodeir, a composer and former Jazz Hot editor, published the original version of his book in 1961, under the title La musique depuis Debussy. The Grove translation appeared in English the same year. It contained chapters covering Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Berg, Webern, Bartók, Messiaen, Boulez, and Barraqué.

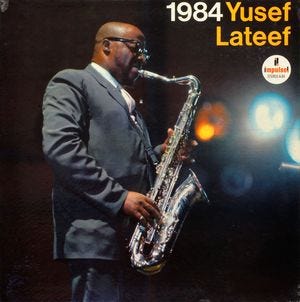

Yusef Lateef, 1984, Impulse! A(S)-84, 1965, LP.

The Yusef Lateef album titled 1984 opened with a twelve-tone piece. Talking to Down Beat the year of its release, 1965, the saxophonist discussed his current conceptions and how they differed from the growing avant-garde movement. "In our group," he said, "there are definite rules to follow which are more flexible than they have been in the past. 'Listen to the Wind' might sound totally free, but there is a definite scheme from beginning to end." This Lateef composition was included on 1984's second side. "The reason the drummer doesn’t play a monotonous rhythm is because he’s supposed to simulate the wind as he plays; it blows at no definite tempo. A piece of paper might be blown along the ground fast and slow; it might even stop at some point. And this is going on during the improvisational course. During the ensemble choruses the drums have a written part where there is silence as well as things to play. As to the actual interpretation of the roles, however, this is up to the individual players. There is a definite, planned vehicle to which all contribute. But completely free playing is meaningless and more than likely to end in chaos. It’s got to be ordered somehow."

I missed this on it's first go round. I love Yusef Lateef and it was fascinating to hear about some of his musical interests and influences.