Some Jazz Records: Paul Bley Clippings (Part 2)

Comments on recordings from musicians and other actors of the jazz scene. Random and not-so-random listening cues from the archives.

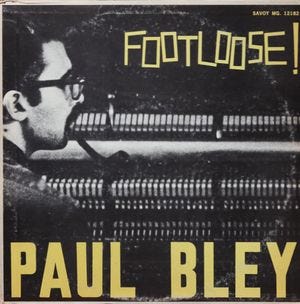

Paul Bley, Footloose, Savoy MG 12182, 1965, LP.

Paul Bley was one of the interviewees in Len Lyons’s The Great Jazz Pianists: Speaking of Their Lives and Music. Asked about ECM producer Manfred Eicher’s assertion that Bley’s 1962-63 Footloose sessions had influenced Keith Jarrett, Bley answered that he would take that as a compliment. "But it’s not difficult to understand what happened," the pianist added, moving the discussion specifically to "Syndrome," the track opening the LP’s second side. "Before 'Syndrome' there were no recordings of piano where the tempo was constant but the harmony was up for grabs—as a procedural matter. Obviously anything that followed that recording would have only that as a reference. Things like that had been done on a horn, but people didn’t expect that kind of flexibility from the piano. You know, I made a practice of never making records of things I knew how to play, but only of recording things I hadn’t yet worked out, the point being that the recording can serve as a learning tool for me. I’ve never done anything long enough to popularize it. With that methodology, I’ve spawned a lot of spin-off bands, spin-off players, and influences. Keith isn’t the first and won’t be the last."

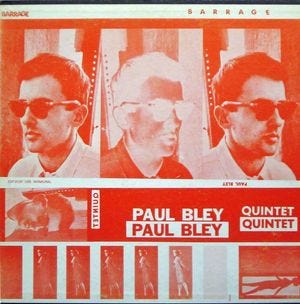

Paul Bley/John Gilmore/Paul Motian/Gary Peacock, Turning Point, IAI 373841, 1975, LP; and Paul Bley Quintet, Barrage, ESP-Disk' 1008, 1965, LP.

In Stopping Time: Paul Bley and the Transformation of Jazz, the autobiography he wrote with David Lee, Paul Bley pinpoints the precise moment when he managed to abandon playing time. "With Ornette, the bass player joined in the fray, but the drummer was always playing metronomic time—not necessarily four to the bar, but at least time. With the advent of Sunny Murray, Paul Motian, and Milford Graves, the drummer joined the bassist in the counterpoint. A lot of players managed to handle the absence of chord changes, although for many of them that was traumatic and still is. For myself, when the drummer gave up playing time, the music sounded totally different than it had the week before. But for a lot of musicians, not to mention a lot of listeners, the music lost all of its meaning." For Bley, the (temporary) move beyond time happened in early 1964, during a gig that bassist Gary Peacock had secured at a Greenwich Village coffeehouse, the Take 3. Bley continued to work in this direction with a different band later the same year. "This quartet from the Take 3 was recorded in March 1964 and later released in the 1970s as Turning Point on the Improvising Artists label. The quintet album Barrage with Marshall Allen, alto sax, Dewey Johnson, trumpet, Eddie Gomez, bass, and Milford Graves, drums, was released on ESP." A more complete version of the Turning Point session later appeared as Turns on Savoy.

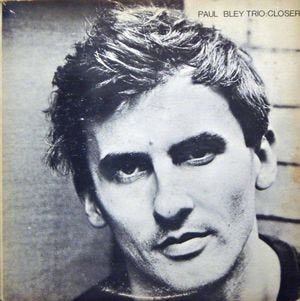

Paul Bley Trio, Closer, ESP-Disk' 1021, 1967, LP.

During an interview he gave to Andy Hamilton for a 2007 Wire profile, Paul Bley admitted a liking for comments in the "at least provocative" register. Discussing his second ESP-Disk' album, which was made from a tape he had recorded on his own in December 1965, Bley provided an example. "I gave [ESP] a four-track trio tape—at the time four-track was the cutting edge," he said. "They 'lost' the bass player. You can hear a bass player, very slightly. So I received acclaim for being so sparse. I’ve never contradicted that, because when I get acclaim, I tend to clam up… Rather than complain about how poorly ESP handled their production, I went with it, and said 'Yes, I am a minimalist.'"

Thanks for turning me on to these albums!