Some Jazz Records: Paul Bley Clippings

Comments on recordings from musicians and other actors of the jazz scene. Random and not-so-random listening cues from the archives.

Paul Bley, Introducing Paul Bley, Debut DLP-7, 1954, 10" LP.

"Free is a relative thing," Paul Bley told Michael Cuscuna in a 1968 Down Beat profile. "On the first album I did with Art Blakey and Charles Mingus in 1953 [Introducing Paul Bley], there were totally free sections with no preconceived ideas. It must have been natural, because that is the way I felt it. I’ve always been interested in challenges in playing." In another interview, given to Jazz Hot's Laurent Goddet in 1971, Bley specified where the free parts—unexpected this early on—of the recording could be found: in the introductions leading to the standards that made up the bulk of the album.

Paul Bley, The Fabulous Paul Bley Quintet, America 30 AM 6120, 1972, LP; and Ornette Coleman, Coleman Classics, Volume 1, IAI 37.38.52, 1977, LP.

One of Paul Bley’s claims to historical fame was to have played at Los Angeles’s Hillcrest Club with the entire Ornette Coleman Quartet as his band, this right before the unit acquired national stature, in large part due to its studio work for Atlantic. "The Atlantic records, once again, were shortened performances," Bley told Bill Smith during an extensive 1979 Coda interview. "Six or seven minutes, which involved a lot of writing. […] But in the club… Those few Hillcrest tapes that managed to come out, with a great deal of duress at one time or another, they’re presently withdrawn from our catalogue. I withdrew that album shortly after it came out. Those Hillcrest tapes are 15 minutes, 21 minutes a tune, as the bebop lengths were. It was a lot harder to listen to microtonal music at length than it was squeezed together between some very friendly songs." Bley had Hillcrest tapes with him in Europe in 1971. He made a great sales pitch during his interview with Laurent Goddet, explaining how the recordings would cast a shadow even on Coleman’s Atlantic masterpieces, because of their length, the horns’s remarkable presence, and the more varied repertoire that also included standards. There was enough material to make between three to six albums, Bley said. A first volume appeared shortly thereafter, on French label America. Bley issued the second and last volume to see circulation later in the 1970s on his own IAI label. It included a take of Coleman’s "Ramblin,'" probably the version he had described to Goddet as "definitive."

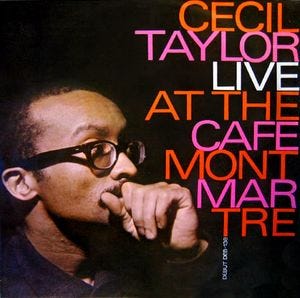

Cecil Taylor, Live at the Café Montmartre, Debut DEB 138, 1963, LP.

While he was playing Europe with his trio in 1965, Paul Bley was interviewed by the French Jazz Magazine. Asked if the new jazz had originated with bassists, the pianist agreed, adding that bass players were the first instrumentalists to have brought something new to the table rhythmically. According to Bley, Gary Peacock, Scott LaFaro and, to some extent, Steve Swallow, were the bassists who stopped playing in 4/4. Former bandmates Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry had made the phrasing of the horns evolve, and a succession of small changes had come about. This, until Cecil Taylor recorded at Copenhagen’s Jazzhus Montmartre in late 1962. It was then, according to Bley, that drummer Sunny Murray found a way to play outside 4/4 that had no beginning and no end, contributing in a major way to the development of the new jazz.

The Coda interview with Paul Bley you have linked is amazing! Thanks for that.