Some Jazz Records: Notes from Mike Johnston (Guest Special)

Comments on recordings from musicians and other actors of the jazz scene. Random and not-so-random listening cues from the archives.

Instead of the usual research material, this edition of our regular column features an original contribution by Detroit-based bassist Mike Johnston. Mike has played with the Northwoods Improvisers since 1976. He was also a writer for Coda magazine between 1981-1999 and hosts the highly recommended Destination Out weekly radio show on WCMU Public Media.

I was invited to write about a few creative music albums that have impacted my life. Like most of you, I too have been moved by Coltrane, Cecil Taylor, Miles, Mingus, Dolphy, Bird, etc. But for this, I decided to focus my attention on records centered around the double bass . Its sound is initially what drew me into the world of jazz. Through the years, my experience has been that the bass is often the last instrument a listener hears and connects with. And this is often also true even of real music lovers. I remember having a cheap record player as a kid (it did have a tube amp) and one day turning the bass frequency off while listening to the Rolling Stones’s "Paint It Black." It made me realize the powerful contribution made by the bass and the drums.

Our band once played a gig to a large group of young blind people. After a few songs, the kids that dug the bass were all lying on the floor, grooving out, and many of the kids that liked the middle- and high-pitched lead instruments were standing on their seats. Uninhibited, they each gravitated to a sweet sound spot in their vicinity to hear the instruments they enjoyed with more precision. It impacted me greatly.

I love bass because it is wood, it’s similar to a tree, and resonates with the tones of the earth. The frequencies from the instrument physically travel closer to the ground. Bass sounds are felt as much as heard, and the double bass vibrates tones close to your body while you play it. It is a sound source that resembles a heart and emanates warmth. It speaks with the voice of the ancients as well as the muffled tones we hear of our mother’s life pulse before birth.

As I’ve aged, the private, intimate, personal, informal, candid, and sacred sounds in music speak to me much more than the fabricated, the spectacle, and the grandiose. Following are a few albums that have helped enlighten me and made my life richer.

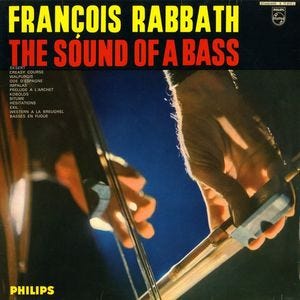

François Rabbath, The Sound of a Bass, Philips B 77.973 L (840.532 BY), 1963, LP.

When I was young, learning and exploring the bass, a bassist friend gave me a copy of this album as a must-listen LP. It chilled me to the bone. There it all was, the bass’s haunting, low-toned, wooden sound world in all its majesty and beauty. Extraordinary playing, musical depth, and rich tone. The instruments used here are only bass and drums (on a few tracks). It truly is "the sound of a bass," a much better title than the one used on the American market version, Bass Ball. It is unlike most other bass-focused albums, with 12 carefully crafted short compositions, and each track painting a vivid (visionary) picture or telling a story. François’s arco playing is singular and precise, even groundbreaking. Merging musical styles of jazz, classical, and Eastern music. Most bassists that I’ve met that know of him hold him in reverence. The track "Prélude à l’archet" ("Arco Prelude") has François bowing with precise lyrical accuracy near the bridge, delivering a melody line an octave above the natural range of the instrument. It is both beautiful and otherworldly, an impossible sound. Years later, Duane Allman delivered a similarly jarring effect on the popular song "Layla," playing lyrical fluid slide guitar lines near the pickups, an octave above the instrument’s range. Interestingly, François’s entire album is tuneful. Most pieces are multitracked, something understandable when you consider how difficult it would have been to find musicians capable of playing the underlying structures of François’s pieces with the vision and precision he plays with. This album truly is an impressive musical journey and a breakthrough LP of bass music. If François had recorded something this hip and original on any other instrument, he would most likely be much more well-known.

[Scans of an interview Mike conducted (through the ancient method of mailed cassettes) with François Rabbath can be accessed in PDF form below. It was published in Coda, June/July 1989, p. 37-39.]

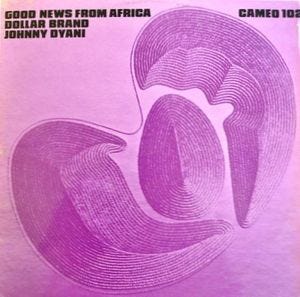

Dollar Brand/Johnny Dyani, Good News from Africa, Cameo 102 ST, 1974, LP.

This is one of the great South African albums. It was created by two musicians who fled the country in the 1960s. They come together here for a totally original duet. Oddly, this was one of the first "jazz" albums that I purchased. I began working at a record store in high school, in the early 1970s. There was a traveling record salesman named Billy Thomas that drove a panel truck everywhere east of the Mississippi River, selling and swapping records and magazines. He was passing through Michigan after a stop in Toronto. There, Abdullah Ibrahim—who still used the name Dollar Brand—had just recorded solo projects for the Sackville label [Sangoma and African Portraits]. Billy had purchased a few LPs directly from Abdullah, including a few obscure African pressings. I hadn’t heard of him and purchased this album based on the title and artwork. It both mesmerized and stunned me. I initially wondered how it was classified as "jazz." The album only features bass, piano, and vocals (with some African flute). The music quickly transforms into a journey into the sacred. Johnny Dyani is a personal favorite as a bassist, but I also find his vocal shouts and cries against Abdullah’s deep rich droning vocal style to be dynamic and chilling. It became an album that I usually spun side 1 of vs. side 2. The tracks on this side move flawlessly into one another and really take you for a wondrous ride through African hymns, spirituals, prayers, folk music, Duke Ellington, and open improvisation. The music feels private and sacred, and I’ve felt at times almost blessed to be able to listen to it. Full appreciation of the music requires contemplation, patience and focus. Slowly, I began to open up to the quality of side 2, which can be summed up by the title of a recurring theme, "The Pilgrim." I now interpret side 1 to be sacred sounds from Africa and the Islamic tradition, with side 2 exploring the musicians’s concept of the sacred music of the West, with much inspiration from Duke Ellington and Jimmy Garrison. In other words, South African musicians seeking freedoms and home via music inspired by a couple of the great American freedom explorers. The musicianship is original, African-rooted, and superb. Abdullah wrote and arranged all of the pieces, but Johnny Dyani is masterful and takes Abdullah’s music to special places where no other bassist could.

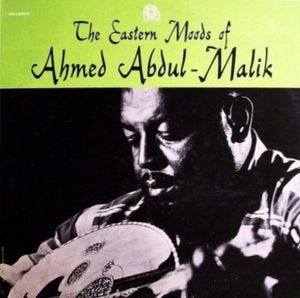

Ahmed Abdul-Malik, The Eastern Moods of Ahmed Abdul-Malik, Prestige PR 16003, 1964, LP.

A highly unique trio album, with each musician playing entirely different instruments on each side, something which had an immediate appeal for me. Ahmed received some recognition with his previous bass work on albums by Monk, Randy Weston, and Art Blakey. With the recommendation of Monk and Trane (Ahmed plays tamboura on Trane’s Village Vanguard recording of "India"), he was able to release six albums of his own music from the late 1950s to the early 1960s. Each was a fusion of jazz, North African, and Middle Eastern music to varying degrees. Only Yusef Lateef comes to mind as someone exploring similar ground in this era. This album is the most unique of Ahmed’s six. I marvel at the fact that it ever got recorded. It strikes me as almost informal music, or a private jam session in a living room. Ahmed had a strong bass tone and came from old school bassists who used gut strings. If you’ve ever wondered what gut strings sound like, listen to the opening track, "Summertime." This version is uniquely solid with a great bass solo. Gut strings fell out of favor for several reasons—they go out of tune easily, they’re quieter, and don’t sing as much when bowed—but it’s a wonderful sound to behold. Many great bassists that are into the rich wooden tones of the instrument still strive to achieve that sound. (A couple other gut string players: Jimmy Blanton, Aaron Bell, Wilbur Ware, early Malachi Favors.) Side 1 of the album features alto saxophone (with a couple of double reed passages) played by Folkways recording artist Bilal Abdurahman. William Allen plays conga and Ahmed is on bass. The overall earthy warm tonal palette is appealing with alto, wood, and skin: i.e., no metallic strings or synthetic drum heads. Ahmed switches to the oud on side 2. His playing is strong and forceful, similar to his bass touch, he really rips hard on the strings. It doesn’t sound like any other oud music that I’ve heard. The pieces jam out with a jazz improvisation sensibility. Bilal switches to the doumbek and is a skilled, tasteful player on percussion. Allen now plays bass, he is no Ahmed Abdul-Malik, but he tastefully lays down rich-toned modal lines for the other players. Historically, Blue Note is held up in high regard—as it should be—for setting quality standards for jazz music. Prestige and affiliate labels often get cast as second best. There are legit reasons for that, but something that I admire about Prestige is that music like this (world music) got captured. Prestige had to know that this wouldn’t sell well. This is something organic and real to the core.

John Lindberg Ensemble, A Tree Frog Tonality, Between the Lines btl 008, 2000, CD.

The album’s title alone suggests something private and sacred. For me, an implied sensibility referencing the sounds of one of nature’s magical musical voices. Having lived many years of my life in tree frog regions, the tree frog song is a seasonal call for the beginning of autumn. When I was a kid, my grandfather called them wood frogs because they lived only in trees. When outside in the forest on a warm late summer evening, their three-dimensional musical symphony is stunning and memorable. "It’s a matter of following the sound." (Donald Ayler quote). I interpret this album’s title as a guide map toward a specific type of musical realm. To begin with, this is a superb "jazz" quartet lineup with John Lindberg on bass, trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith, saxophonist Larry Ochs, and Andrew Cyrille on drums. This isn’t free jazz or chamber music, it is cool music in the sense of a great Bill Evans or Lee Konitz sophisticated serene moment. This description is not meant to portray this as a bop album in any sense. Each musician is a master of high-level intricate lyrical passages and of sensitive open (free) organic interactive ideas. The musical pieces (mainly by Lindberg) are on par, constantly weaving in and out of thoughtful moods, concepts, themes, rhythmic pulses, long lines, interplay, fire, and delicacy. The album is diverse and consistently great. I prefer to listen to it as a suite rather than broken down to individual tracks. I have, however, listened to the beautiful Lindberg/Smith duet "Dreaming At…" alone in quiet late night settings: it is precious music in the best sense of the word. The pieces never sonically overwhelm you, they are inviting, with every note played with precision, soul, and delicacy. I consider the music to be visionary, personal and private. Fortunately, it is also recorded well, allowing us to experience its subtle nature. This is some of my favorite playing by each of these extensively recorded musicians. Since I’ve made a primary focus on the bass in my album selections, I’d like to add that John Lindberg is a great bassist and fun to focus your attention on. He has rare air arco chops in the same league as François Rabbath (each with their own personality) and overall musical talent that allows him to interplay passages and melodic fragments with everyone at lightning speeds. He’s fluid, agile and plays with great finesse, like a fine-tuned athlete, which doesn’t mean that he doesn’t also hold down and ground the music in hip ways when it needs it. This is total bass playing in all of its wondrous forms.

I’ve taught music history courses for over 20 years. I try to focus the classes around carefully listening to music, and I try to help students develop tools to connect with it. I can’t tell you how many papers I’ve read that begin with the phrase, "I listened to the first 5 seconds and decided that I didn’t care for the song…" As if that was supposed to inspire me to want to read on. Each of us has been guilty of cutting these types of corners when sampling music. Some things that appeal to us, we know instantly, but more times than not, greatness is revealed by repetition, familiarity, understanding, and exposure. A paraphrased quote that I often try to keep in mind is, "Don’t mistake the surface perception for the entire reality"… As often as I have engaged in music, I believe that this quote heavily applies to this recording. I found that it takes time, calm and a proper environment to connect with this wonderful album. It is like stepping into the night songs of the tree frogs themselves.

Honorable mentions:

Dave Holland, Conference of the Birds, ECM 1027, 1973, LP.

This album received a lot of spins on the turntable back in the early 1970s. There are several wonderful pieces and arrangements. Braxton and Rivers play well together. And Dave Holland is stellar because he’s Dave Holland. When I revisit a lot of the releases from this era this album continues to deliver. If fusion music hadn’t taken over so much, this could have been one of the guiding light albums of the era.

Ronnie Boykins, The Will Come, Is Now, ESP-Disk' 3026, 1975, LP.

An incredibly diverse recording definitely in the soundscape of Sun Ra. It also has an enigmatic Sun Ra-esque title. This unique album is full of the unexpected, with three under-recorded front line horn players (James Vass, Monty Waters, Joe Ferguson). Most Sun Ra fans have a favorite Arkestra member. Pat Patrick and Ronnie Boykins are a couple of mine. I love Boykins’s relaxed playing approach with great sound and tone.

Great choices and great article. Thank you Mike

Very nice, Mike. I was particularly touched by the story of your gig playing for young blind people and their response to your music.