Some Jazz Records: Cecil Taylor Clippings

Comments on recordings from musicians and other actors of the jazz scene. Random and not-so-random listening cues from the archives.

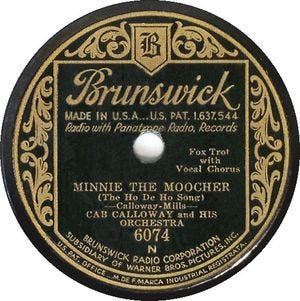

Cab Calloway, Minnie the Moocher/Doin' the Rumba, Brunswick 6074, 1931, 10" 78 rpm.

Cecil Taylor discussed his 1930s childhood in A. B. Spellman’s Four Lives in the Bebop Business. "It’s good that I studied percussion," Taylor said. "See, percussion has always been a big influence on my music, as I think all the critics have pointed out. About this time I started hearing Gene Krupa and Chick Webb. Chick Webb [whom Taylor saw at the Apollo] was an especially big influence on me. When I was about six or seven [ca. 1935-36] I used to take out the pots and pans and beat on them after digging Webb. Same with Cab Calloway. I’d hear him and start running through the house screaming 'hidihidihidihi,' shaking my head and trying to make my hair fly, though of course it wouldn’t." Calloway’s well-known "hi-de-ho" catchphrase was used in a number of contexts, the most famous remaining his original 1931 recording of "Minnie the Moocher," reputedly the first million-selling disc by an African American artist.

(illustration unavailable due to the recent DDoS attack on the Internet Archive)

Fats Waller and His Rhythm, Blue, Turning Grey over You/Honeysuckle Rose, Victor 25779, 1938, 10" 78 rpm.

"Among the names, it’s hard to say, but I’ve always liked Fats Waller," Taylor tells Valerie Wilmer in her Jazz People book. "As a child I suppose you like these people partly because they’re entertaining or bizarre or strange, sort of like a bad dream or a very funny dream, and Fats was always funny. I remember him playing 'Honeysuckle Rose' once and hearing the kind of impulse that the piano had, or impulses separate from pulse, you know. Everything he did seemed to be done before it actually was done and it seemed to color everything that the other musicians were doing. There was this kind of feedback, and I suppose it was really my first awareness of the kind of exchange that happens between jazz musicians." Certitude about the exact recording heard by Taylor is probably lost to history, but Waller’s 1937 instrumental version would be a possible guess as it contains significantly more interplay than his 1934 vocal rendition.

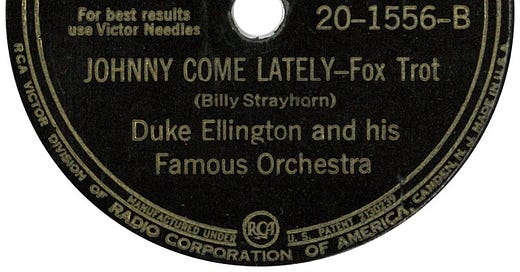

Duke Ellington and His Famous Orchestra, Main Stem/Johnny Come Lately, Victor 20-1556, 1944, 10" 78 rpm.

"Ellington’s '42 records I will always dig. God what a band," Cecil Taylor added as a postscript to a letter written as a young conservatory graduate (see Allan Chase’s research). Toward the end of his life, talking to The Wire, Taylor still listed "Main Stem" and "Johnny Come Lately," two pieces recorded by Ellington in 1942, among examples of masterpieces. The latter, penned by Billy Strayhorn, was one of the few pieces by a composer other than himself that Taylor recorded. "I consider myself an outgrowth of all the important jazzmen who have gone before me," Taylor said in a 1964 Liberator article. "But, Duke Ellington is the most important influence in my music. Duke is the greatest historical figure in jazz, and his orchestra is the most important organization and musical sound in jazz. His orchestras have shaped all that is important, all that has come out of jazz."